This script is from a talk given on the University’s Diversity Day 2017.

Where are you from? What part of Germany? Of Europe? Of the world? Do all Germans speak the same language? What influence does this have on your impression of them? Why? What is your reaction to foreigners who have worked to learn German? How much do you care if their German is not perfect? Or too perfect? What do you think native English speakers think about your spoken English?

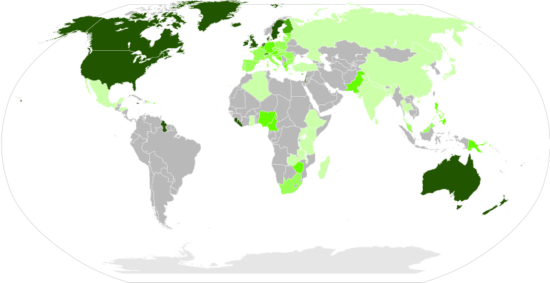

English is currently used as official, semi-official, or special-status language in more than 70 countries worldwide. In some cases, such as in the U.S., English has no official dominant status, but is spoken by a mother-tongue majority. In the year 2000 it was estimated that English had 400 million first-language, 400 million second-language and 700 million foreign-language speakers, giving us about 1.5 billion English speakers around the world. That was then one quarter of the global population. Note that mother-tongue speakers are in fact in the minority. The influence of second- and particularly foreign-language speakers is growing exponentially thanks to the globalization of communications, business and academia. Indeed, the vast majority of English speakers worldwide are bi- or multilingual, and speak a recognized variety of English that may or may not meet usual standards. This means that not only linguists but even language teachers worldwide are starting to adapt their expectations and standards.

Going back in time, the language had its own diverse origins from the very beginning. Famous author Daniel Defoe once wrote of ‘Your Roman-Saxon-Danish-Norman English’. He was referring to the multiple, repeated invasions of the British Isles by Continentals from both north and south. The native Celts and the earliest invaders, the Romans, in fact had little influence on the common language, with the exception of a few place names, but the Germanic tribes, the Angles, Saxons and Jutes, brought their languages into the lowlands and spread them across the fertile islands to merge and become Old English (also called Anglo-Saxon). The Vikings came after, invading the coasts over nearly 300 years, and bringing Danish and Norwegian. Christian missionaries arrived in the same period, bringing additional Latin influence. Every one of these conquests brought more to the English language, leading to the co-existence of words from the Germanic tribes (whale, heaven, father), from the Christian missionaries (temple, tiger, offer), and from the Vikings (sky, knife, husband).

In 1066, the Normans famously conquered England, and brought on the emergence of Middle English, not only with a vast array of loan words, but with grammatical developments and morphological simplifications as well as spelling and pronunciation shifts. Starting in the 15th century, the age of printing conventions and standardization brought about the establishment of Early Modern English. It was no longer extended or intense exposure to other languages which brought color into the language, but new-coined phrases stemming for example from William Shakespeare, technological developments which required new terminology, and of course the spread of the printed word, which selected the London variety as its standard. It was not until later that colonialization brought significant new lexical contributions back to English soil and the English language. Since then, however, we have been able to observe several other sources of loan words: Indian, West Indian, and, perhaps astonishingly, American.

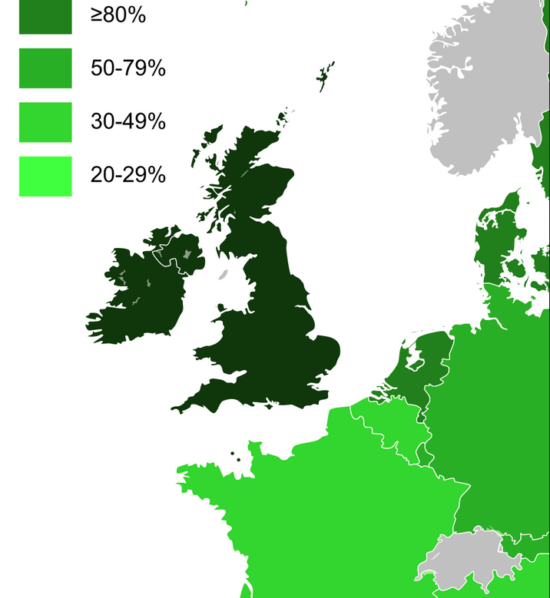

Before addressing this last, perhaps a word on language variety upon the British Isles. Thanks to the multiple invasions by different cultures and languages, thanks to influences from Latin and Celtic/Gaelic/Briton, there is a huge variety in the English language within a very small space. In a land no larger than Austria you will find enormous differences not only in colloquial vocabulary, but also in pronunciation, rhythm and even grammar, sometimes to the point of mutual unintelligibility. Even disregarding Scots and Irish Gaelic, disregarding Welsh and Manx, one can travel just 50 kilometers within England and find that the accustomed dialect is no longer valid. The English are proud of their regional dialects and proud to be able to recognize another’s place of origin based on their accent or choice of words. While children learn a standard version (not Queen’s English, but RP) in schools, most jealously guard their spoken language against outside influence as part of their identity. It ought to be noted that social class has as much effect on an individual’s speech as origin, based not only on education levels, but also on (kinds of) institutions.

Variety within the enormously larger North American lands is not nearly so great. Additionally, instead of being drawn along geographical lines, the greatest variation is found in social subcultures such as among urban Blacks or in more isolated groups, for example in the Appalachian communities (which incidentally are said to still speak a dialect closest to what Shakespeare wrote). Otherwise, language here is mostly affected again by language contact among immigrants or by technology and the resulting neologisms.

So, back to international English. Of course, English was subject to influence not only by dominant invaders, but also by the languages which it itself invaded. By looking again at the world map, we can see much of what happened there. It is of course the British Empire to which we can attribute the global spread of the English language. In about 2000, over 315 million speakers were counted in North America, Britain’s largest legacy. With the unfortunate exceptions of the USA and Australia, in every British colony, English was, and continues to be, heavily exposed to and influenced by native and other languages. In addition, in the natural evolution of that organism called language, the English spoken even in those relatively homogenous/monolingual environments changed and grew. Thus, American and Australian English became distinct from British English not only in pronunciation but also in lexis, spelling, and grammar. Still, these varieties continue to have more in common than not.

At the same time, speakers of those standardized varieties are starting to notice a global trend thanks to the influences not only of the expected contact languages in former colonies but also of languages all over the world. Not only are more and more people deciding to learn English, but they are also using it in global communications, whether they are making business deals, chatting online about their favorite television series, or collaborating with other nationals on research projects. What is developing out of that? Linguists are beginning to recognize new varieties of English. The English spoken in India, Ghana, Singapore, or South Africa tends to be quite different from that spoken in the U.S. or Great Britain. It is pronounced quite differently. It manifests a different rhythm. It has absorbed vocabulary and syntactic patterns that distinguish it from the standards taught in schools. Still, it is English. Nowadays, it is fashionable among linguists to speak of ‘World Englishes’ and to study these varieties as fascinating manifestations of historical-, contact-, and sociolinguistics.

Additionally, new technology as well as the global spread of English-language pop culture are not only leading to new concepts and new words for them, but also increasing the contact among speakers of different languages and varieties, leading to more borrowing and more influence. On top of that come new conventions applied to overcome the limitations of electronic communication. Emoticons are the hieroglyphics of the present, and, yes, they are being studied as a language. Last but not least, social change is also a motor for changes in the language. Language that was once considered simply grammatically incorrect is now the only way to express inclusivity. Some linguists have begun to see English as a prototype category, with different varieties showing overlaps, fuzzy boundaries, and smaller or greater distances from the central instances.

Also language teachers, somehow inherently progressive, are beginning to address the issues manifested in the interaction between language and identity. A big part of what that means is not imposing majority or foreign standards on the speakers in their classrooms. It means recognizing the varieties used by their learners as, indeed, acceptable uses of the language. It means acknowledging the diversity of their pupils. It means that while they model, and teach, standard varieties, they accept (at least in speech) common usage embodied by their pupils. In some cases it even means exposing learners to other varieties of English, and not only that spoken by prototypical British and North Americans.

So, what does this mean for you as speakers of English as a Foreign Language? What does the English you learned in school have to do with what you use English for now?

- First of all, the purpose of your international interactions determines to a vast degree the amount and kind of English you need. For oral communication, there is no need to learn language beyond the specialist vocabulary and conventions used within your field, which you tend to know already, and perhaps enough to make small talk or navigate the way to a convention in a foreign country.

- Secondly, how many of your interlocutors are native English speakers? How many of them will notice or care if you get your verb tenses a little mixed up, leave out the article, or choose a word which has a different connotation, as long as you are able to get your meaning across?

- Finally, most English speakers are

- Impressed with your mastery, and

- pleased that you have learnt their language, so they don’t have to learn yours!

On the contrary, monolingual English speakers tend to assume that others will learn / have learnt some of their language, but still respect it at the same time. Most have tried to learn another language but not gotten far, since school requirements are minimal. Almost all recognize the effort put in to acquiring a foreign language and appreciate that you have made it easy on them.

While everything I have told you applies only to spoken, and not to written English, I hope it will rest your mind that there is not as much to worry about as you might have felt so far. Language is diverse, and it is an expression of diversity. It is individual, and an expression of individuality and identity. Conventions play a role within communities, which are also a substantial part of identity, but they are limited, and easy to learn. Think of them as an aid, not an obstacle.

Remember, as Immanuel Kant once posited, “Alle Sprache ist Bezeichnung der Gedanken.’’