Vowels might be considered the most significant parts of language pronunciation, as they are frequently the part that surprises us in that differences in vowel pronunciation make mutual intelligibility more difficult. They are particularly important for the rhythm of English, so it is recommended that you read/watch this before addressing that key topic to Standard and other English varieties.

Just for fun: pre-viewing task

Go for a search on the World Wide Web. Look for a resource that appeals to you specifically for getting audio input to help practice listening to and acquiring the sound of English. It could be a podcast, video channel, or anything else relevant. Please post your results here in a comment below. The link and a one-sentence description are sufficient: make it as user-friendly as possible; these resources are for you readers!

Then, have a look at the video or the text below for some information about vowels in English.

Describing vowels

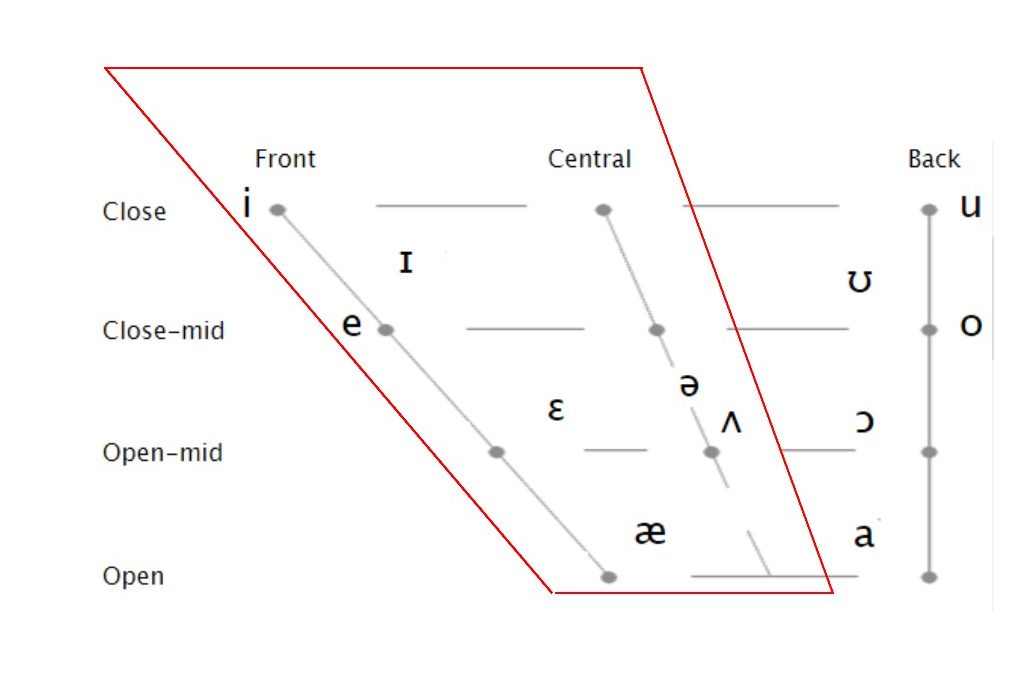

Vowels are less easily described than consonants because there are no distinct boundaries between them as there are for consonants, and so they are usually described according to how they sound in relation to each other. Unfortunately, any phoneme can still vary quite a bit, and still count as an instance of that phoneme. Vowels in particular may vary in length, roundedness, pitch or nasality without becoming unintelligible. The clearest distinction found so far is the one found here: The vowel chart below shows the approximate positions of the tongue during the articulation of various vowels (here those of Standard American English).

Front, Central, Back: refer to the part of the mouth where the tongue is raised the highest when a particular vowel is pronounced. For example, when /æ/, as in “cat”, is pronounced the highest part of the tongue is in the front of the mouth (though the tongue is not raised much at all for this vowel).

High, Mid, Low: indicate whether the tongue is raised higher, about the same, or lower than when it is in its “resting” position. For example, when /tu/ as in “to”, is pronounced, the tongue is raised higher than its resting position.

Lip position: the vowel chart does not indicate lip position, but this is also one of the parameters needed to classify vowels. Lips are either rounded or unrounded but rounded lips can be lightly rounded, and unrounded lips can be spread or neutral). The front and central vowels as well as the back vowel /ɑ/ are all unrounded. /u/, /ʊ/, /oʊ/ and /ɔ/ are all rounded.

Tension: the amount of tension you can feel in your face as you pronounce a vowel (particularly when you pronounce it individually) is another thing that distinguishes vowels. Those on the outside of the chart, i.e. /i/, /u/ and /oʊ/, are tense, while the others are lax.

Length: vowels are also distinguished by how long they are in pronounciation, which is often connected to both tension and position in mouth. In IPA length is sometimes (largely by British speakers/linguists) identified with the help of a length diacritic that looks rather like a colon, as here: /iː/. Because our digital format make that more complicated than necessary, and in fact the existence of separate phonemic symbols is already a distinction — for example — between the short /ɪ/ and the long /i/, we have decided to do without those in this blog. Just be aware that other sources may look slightly different for that reason. Here a brief overview of how our usage may differ from that of others.

Keep in mind that the vowels in the chart are phonemes, meaning that they are approximations. For example, “beat” can be said in a relaxed way or very tersely, and the vowel sound of the first way will not be identical to that of the second.

Front Vowels

You’ll see in the chart above that there are four pure vowels considered front vowels, which are distinguished by the height of the tongue, or, more obviously, by how open your mouth is when you pronounce them. Thus, /i/, /ɪ/, /ɛ/, and /æ/ are the front vowels in ‘descending’ order, i.e. from most closed to most open. You can try producing the sounds one after another and feel how your jaw drops from one to the next. Listen to the recordings here and repeat.

| Phoneme | example(s) in English | Play sound Irish English and USA English |

|---|---|---|

| /ɪ/ | sit, in, fringe, gym, lid | |

| /i:/ | eagle, perceive, sea, friendly | |

| /e/ | friend, left, bury, berry | |

| /æ/ | mad, laugh, academic, vary |

While L1 interference from some southern European languages means that English learners have to learn that not every letter i sounds like /i/, many other speakers struggle to distinguish /ɛ/ from /æ/. Unfortunately, this can lead to some misunderstandings, as when had /hæd/ is confused with head /hed/. Of course, it is particularly confusing when the word had is unstressed and reduced, and sounds even more like /hɛd/; then we have to rely on context to understand what is being said.

You can practice both understanding and producing the two phonemes in these interactive exercises. To test your understanding of the concepts here, these exercises will also be helpful.

Central vowels

The central vowels, as their name suggests, are pronounced in the center of the mouth. The lips are relaxed and unrounded, the tongue raised to mid height in the center. The distinction between /ə/ and /ʌ/ is not really noticeable for the most part. They are simply used to establish if the phoneme/ syllable is stressed or not, but the pronunciation is the same: try the classic word above, which contains both: /əbʌv/ . Many linguists and even some transcribers in fact employ only the phoneme /ə/ unless they are particularly interested in the use of stress in the recorded language.

| Phoneme | example(s) in English | Play sound |

|---|---|---|

| /ə/ | about, haven't, honor | |

| /ʌ/ | utter, mud, double |

In particular the unstressed vowel is so significant as the unmarked central vowel that it has its own name: schwa. This is the most neutral of phonemes in English, with the mouth only slightly open and the tongue in the middle of the mouth. It occurs most often as well, and is usually very short (or sometimes disappears altogether as in middle /mɪdl/. Think of speakers of Standard Englishes (particularly the American varieties) as lazy, wanting to do as little as possible when speaking. You can find out more about that in the upcoming segment on rhythm in English pronunciation. For now just remember that unstressed schwa can be represented by nearly any (vowel) letter and occurs multiple times in most sentences.

If some of this information seems overly technical, general basic concepts of phonetics and pronunciation are dealt with in another post. You can find exercises on the points introduced here in the practice section.